Since the outbreak of the Bulgarian protests in the summer of 2020, Bulgarian political issues have become more and more similar to the Romanian ones. The similarities are not just related to the aspirations of the Bulgarian middle class to replace the dinosaurs of the transition through the anti-corruption fight. Nor are they limited to the adoration shared with the Romanian middle class for the “anti-corruption martyr”, Laura Kovesi, who was driven out of her homeland, but found refuge in the European Prosecutor’s Office in Luxembourg. They are not even based on the intrusive repetitions of the BSP leader, Cornelia Ninova, that in the person of Boyko Borisov she is fighting a “parallel state”. This term was used by the former strong man in Romanian politics, Liviu Dragnea, to refer to his opponents in the secret services. It is not particularly appropriate for the Bulgarian realities, where Borisov is the centre of the system of government, not parallel to it. The general game in Bulgarian politics is increasingly similar to that in Romania in 2017-2019, when the middle class convened mass protests against the ruling Social Democrats, and they responded by making financial gestures to the disadvantaged masses and reducing taxes on consumption.

As I stated in an interview with Bloomberg Bulgaria TV in January 2020, the Romanian Social Democrats used fiscal policy to create their own influence in business circles that have different interests from those of the so-called “corporatists” – employees in multinational companies. In addition, the Social Democrats increased the incomes of teachers, doctors and public sector employees in several waves of wage rises. This is how they secured their public influence. This has put pressure on the private sector to keep raising wages so that it is not exposed to a staff exodus. And that is how gradually the dispute between the two major camps in Romanian politics – the technocratic and the politico-oligarchic, led to increased revenues, higher consumption, and significant GDP growth. Combined with the increase of foreign investments, they gave strength and confidence to Romanian citizens. At that time, there was apparent stability in Bulgaria; the government was not challenged by anyone, and any sporadic protests disintegrated or their demands were met before they gained strength. Time seemed to stand still. The Bulgarians were either satisfied or too disappointed to take any public action.

Now it seems that the roles are being reversed. In Romania, confrontation has disappeared. Dragnea went to prison in May 2019. In the autumn of 2019, the Social Democrats lost power to the National Liberal Party, which is a member of the European People’s Party and has European support. This support is a key factor in the context of the coronavirus crisis, when European funds are crucial to support the economy and health systems. In the December 2020 parliamentary elections, Prime Minister Ludovic Orban’s conservatives are expected to win by a significant majority.

Meanwhile in Bulgaria, there are two major political currents – for and against Borisov, for and against Geshev, and things have started happening. Our confrontations meant money for pensioners, the unemployed, public sector employees, social services, education and the health system – or at least promises. At this moment, like the Romanians in 2017-2019, we are captive to our internal confrontations and we criticize every action of Borisov, Hristo Ivanov (the leader of a segment of the protests) or of any of the other participants in the political game, according to our personal preferences and prejudices. But we do not always realize that in the face of political competition GERB can no longer expect to win elections without any effort. Boyko Borisov must give more to the people to create additional electoral support, just as the Romanian Social Democrats supported their clientele networks with financial gestures at a time when their president was the baron of Teleorman County, Liviu Dragnea.

At the end of his third term, Borisov has found himself in a similar situation to Dragnea’s – having to work to expand his base beyond the middle class, which has actually divided into his supporters and opponents. It is worth remembering that previously the middle class stood united behind him, and he offered social stability and conditions for the development of those who were successful during the transition. The urban right is now on the streets, but it was a coalition partner in Borisov’s second government.

Borisov and Dragnea are similar in their approach to countering the dissatisfied middle class attack. However, they are in different structural positions. Borisov is a veteran EU prime minister, well received in European People’s Party circles (as seen during talks on the resolution of the Bulgarian political crisis in October 2020 in the European Parliament). The positive reports of the European Commission on the state of the rule of law in our country in the last two years have been a sign of GERB’s lobbying influence in the European institutions. As for Dragnea, he bet on military acquisitions in the US (gestures to Donald Trump and his administration) and gestures to Israel (he tried to move the Romanian embassy in the Middle East country from Tel Aviv to Jerusalem), while it was particularly obvious that Western Europe was extremely sceptical of his judicial reforms. In Romania itself, Dragnea won several battles (for example, removing Laura Kovesi from the leadership of DNA), but a war with the technocratic sector is unlikely to be won in the EU – and this was seen when Dragnea went to prison the day after the European elections in May 2020. Therefore, the current confrontation between the urban right, which has positions in the European technocratic institutions, and Borisov’s government is interesting and may be the first real threat to the political system of Borisov’s time.

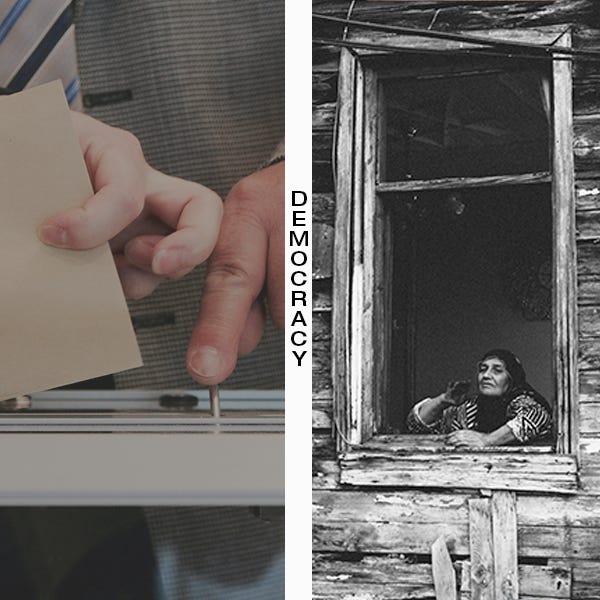

The Bulgarian situation is reminiscent of the Romanian one in other respects as well. The label “beautiful and smart”, which the Bulgarian protesters were given or used about themselves in the summer of 2013, has a direct equivalent in Romanian politics. It is about the so-called TFL-ists, the abbreviation of “beautiful and free young people”. This is the name for young professionals, for young people in creative professions, with the self-confidence that they are informed, capable and well paid, who feel they are the elite compared to the “ugly and bad” masses. This feeling repulses some older Romanians and those who live outside the capital and big cities. Obviously, these are two worlds – some have graduated from high schools and universities (often in the West), live in urban centres and are part of the middle class, while others are on the social peripheries – in big city housing estates and in rural areas. These objective and subjective differences are now being used by the Bulgarian government.

“With all due respect to young people who don’t like us, (let me say that) we don’t like them,” says Boyko Borisov. And indeed – some people say they are not from GERB, but they are categorically against what Hristo Ivanov, the leader of the young generation party in politics, Yes, Bulgaria, represents. Not coincidentally, Ivanov’s public appearances are scrutinised and any suspicion of deceitfulness is gossiped about for days on social networks. It seems that the usual polarisation of Central and South-Eastern Europe between Trump and Soros supporters is also used discursively in the current protest, as in the words of Deputy Prime Minister Krassimir Karakachanov, protesters want a “gender republic” (which seems to mean a society where LGBT people, feminists and gender studies experts are able to enjoy life, insead of being supressed).

The search for parallels between Bulgarian and Romanian politics can continue with the youth party in Romanian politics – the Save Romania Union (USR) and the Bulgarian equivalent – Yes, Bulgaria. Both have a middle class and corporate base, have anti-corruption as their dominant theme and are accused of not being socially sensitive, but of finding solutions to society’s problems in a stronger private sector. USR is an ally of Dacian Cioloș’s Plus party – a party with several leaders from older political generations, who, however, have connected with and supported the young people. For its part, Yes, Bulgaria is in alliance with the party of some old elites – “Democrats for a strong Bulgaria”, which comes from the group around former Prime Minister Ivan Kostov. In Romania, USR is so influential that it is taking away from the strength of the Romanian Greens, who remain with modest electoral support. In Bulgaria, Yes, Bulgaria is not as strong as its Romanian counterpart, but the Bulgarian Greens are relatively well supported by the younger generations.

In September 2020, I stated in an interview with the Danish organization Democracy in Europe that the Bulgarian middle class wanted to feel empowered to fight corruption and therefore were protesting against the current attorney general, who is seen by them as a defender of the oligarchy. The Romanian middle class protested in 2017-2018 in defence of Romanian prosecutor Laura Kovesi, because due to her actions, the dinosaurs of the transition had to leave the political scene, which opened up a space for new blood in it. The golden age of Romanian anti-corruption coincided with the founding of the Save Romania Union, which began with protests against the gold mining project Rosia Montana in 2013. Unlike its Romanian equivalent, Yes, Bulgaria did not emerge from street demonstrations that gradually grew into a civic and political movement. Street pressure appeared in Yes, Bulgaria’s agenda only later, with the confrontation over the control of justice and the rise of Ivan Geshev in the prosecutor’s office.

However, politics is too complicated to describe and judge so easily, just by saying that we are seeing a celestial confrontation between two elites: the young and good against the old and evil who must be eliminated. This ambiguity is also shown in the “evil” social democrats of Dragnea’s time, who also had their own criteria for good and evil in society. They used fiscal policy to divide Romanian capital into two types – useful, productive and harmful, speculative. In December 2018, the Social Democratic government introduced the so-called “greed tax” – the taxation of the assets of financial institutions if the ROBOR interest rate index exceeds 1.5% for a quarter or half a year. This was because, according to the then government, many foreign companies used tricks to avoid paying corporate tax. The provisions of the greed tax have been rewritten by the government of Ludovic Orban so that it no longer creates any burden on the financial sector. But the Social Democrats have never taken action against the car industry, which is highly developed in Romania. In addition, Dragnea’s people exempted a large sector of the IT specialists from paying income tax – another measure to support the production side of the business.

Starting in 2013 with the special VAT rate on bread, the Romanian Social Democrats reduced VAT on a number of products in the following years, while increasing wages and pensions and thus increasing consumption. This was one of the reasons for the significant economic growth in Romania during their rule. Due to their tax changes, 9% VAT is charged on orthopedic products; medicines for humans and animals; food and drink (except alcoholic beverages); water when used for irrigation in agriculture; fats and pesticides used in agriculture; seeds and other agricultural products, as well as agriculture-specific services; water supply and sewerage. A special rate of 5% VAT is used on textbooks, books, newspapers and magazines; for tourist services, catering, for access to cities, museums, memorial houses, historical monuments, architectural and archaeological monuments; hotel accommodation, restaurant services (except alcoholic beverages other than beer), use of sports facilities, transport by train, lifts; and the construction of social housing.

Currently in Bulgaria, the government also uses fiscal policy to gain social influence.

However, it is making gestures to businesses rather than ordinary consumers. For years, the Bariccade has shown that taxes in Bulgaria are low for businesses, but high for workers and consumers. In November 2017, more than 30,000 Bulgarians demanded the introduction of a non-taxable minimum and a special VAT rate on essential products. Business tax support has a clientelistic element, as employers can train their employees to vote for the right political force in the upcoming elections. But reducing the taxes of ordinary people through a fiscal policy that leaves them a little more money in their pockets would mean empowering the common man without a binding commitment to vote for you. Based on current and future government action, we can judge who to rely on to receive electoral support.

The parallels between Bulgarian and Romanian politics do not end here. The topics are similar in terms of international relations. Both sides are at the forefront of US attention in our region – both are discussing the construction of US-assisted nuclear power plants, are expected to transfer US troops to our area to control Russia and possibly Turkey, and both Sofia and Bucharest are buying weapons from the United States. The same debates are taking place on social networks for and against Trump and Soros.

Isn’t it time for Romanians and Bulgarians to overcome their prejudices and indifference towards their neighbours and realize that they live in a similar reality – a precondition for a more active interaction between them? Obviously, the Bulgarian political elites are informed about what is happening in Romania and are inspired, taking concepts and policies from the Romanian context. It remains for ordinary Bulgarians to show curiosity about Romanians. Knowing them, we can better understand what is happening in our own country.

Photo: The banner is demanding a “European federal prosecutor’s office”, a claim related to the mythology around Laura Koveşi as chief prosecutor of the middle class (source: Nikolai Draganov)

The Barricade is an independent platform, which is supported financially by its readers. Become one of them! If you have enjoyed reading this article, support The Barricade’s existence! We need you! See how you can help – here!

Warning: Undefined array key "layout_mood" in /home/klient.dhosting.pl/bcdmedia/thebarricade.online/public_html/wp-content/themes/viewtube/header.php on line 116