This article is signed by Cornelia Hildebrandt, who is the vice director of the Institute for Critical Social Analysis of the Rosa Luxemburg Foundation (RLS) and its consultant on parties and social movements. She is responsible for the structuring of party research within the foundation as well as the development of the ‘Left Politics’ project as part of transform! europe. She is the RLS’s specialist on issues regarding ideological dialogue.. The article was published on 24 April 2020 on the site of Transform!Europe network and is part of Transform’s discussion on the future of the European left. It came out first at the website of the Rosa-Luxemburg-Stiftung (full version).

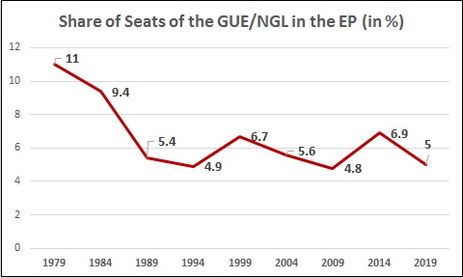

The Party of the European Left (PEL) — alongside the European United Left-Nordic Green Left (GUE/NGL) in the European Parliament (EP) — is one of the European left’s most prominent transnational organizations.

What challenges does it face? What are ist potentials for future developments?

On the role and self-conception of the Party of the European Left

The PEL is a party of parties. Individual memberships are possible, but have no significance for the time being. It includes 30 member and observer parties from 25 countries, of which eight parties are currently members of the 39-member GUE/NGL.

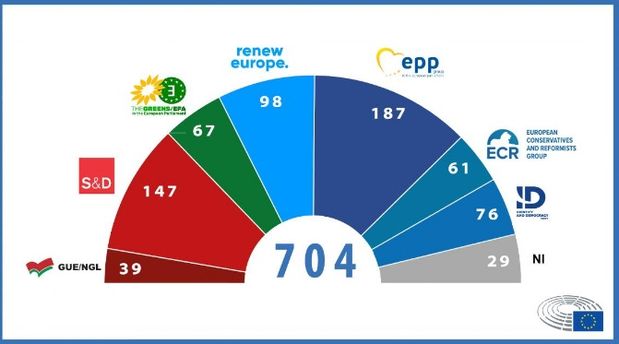

Current distribution of seats in the European Parliament

At the national level, the PEL has 291 members in parliament (as of January 2020), more than the Greens (237 seats), for example. However, this parliamentary presence is concentrated in 12 EU countries, in particular Greece, Spain, Portugal, Germany, Finland, and Cyprus, whereas more than half (16) of the parties within the PEL are not represented in parliament.

The Party of the European Left unites completely different parties that have different functions in their respective countries, and correspondingly different expectations: it should develop its capacity to act at a European level, provide European solidarity and support for left-wing parties of government where applicable, and at the same time bolster the more marginalized left parties.

Despite being a minority within the PEL, communist parties still influence the party’s development. These communist parties are, of course, transformative, pluralist left parties which have undergone significant processes of renewal since 1989. Most of these parties see themselves as pluralistic parties or party alliances, in which the former communist parties have either been absorbed into new party projects or continue to exist alongside them as an independent current or structure.

The parties of the PEL have a reform-communist, left-socialist, left-social democratic self-image that does not exclude participation in left or centre-left governments. It takes influence from the values and traditions of socialism, communism and the labour movement, feminism, the environmental movement, and sustainable development, peace and international solidarity, human rights, humanism and anti-fascism, progressive and liberal thinking, both nationally and internationally. Their challenge is to cultivate this diversity in a way that enables them to act transnationally. What difficulties and challenges do they face in this task?

Problems and challenges

Thesis 1:

Since 2014, the political momentum has shifted away from left-wing parties towards the Greens and increasingly towards the political right, which is also regrouping on a European level.

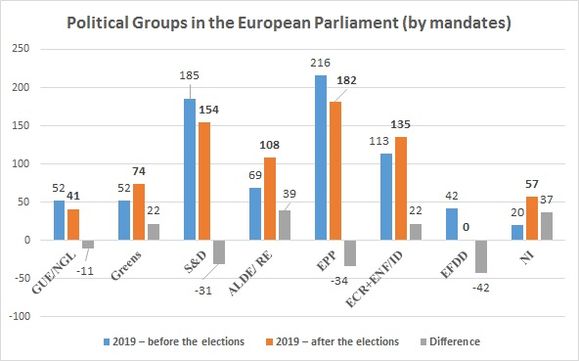

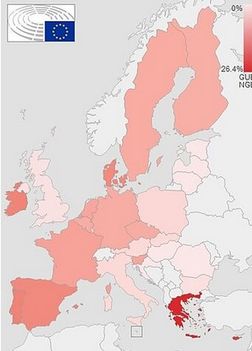

In contrast to 2014, political debates are no longer dominated by left-wing struggles against austerity policies. Climate change, the treatment of refugees and migrants, and the prospects of the EU in the face of Brexit all suggest changing lines of social conflict as well as a shift in discourse within the EU, and the parties of the left are hardly visible in these contexts. Despite the left’s good and stable electoral results in Greece, Spain, Portugal, as well as in Belgium and Slovenia, these parties lost in the 2019 European elections. With a total of five percent of the votes and 41 delegates, they form what is now the smallest group in the European parliament, while the Greens and the right are on the rise.

See: transform! europe‘s post election country analyses (EP19 Monitoring Project)

In the Northern and Western EU countries, left parties are stagnating with between five and ten percent of the vote—this is the case for Die Linke in Germany and La France Insoumise and the French Communist Party. In the Netherlands, the Socialist Party (SP) fell below five percent in the European elections. The Scandinavian left parties also lie between five and ten percent, despite slight gains in both the European and national elections in 2019. Finland’s Left Alliance was part of a six-party coalition, but did not want to take responsibility for austerity measures and left the government 2011, before returning after the 2019 elections. Similarly, the Danish Red-Green Alliance has a mixed record in terms of supporting minority governments.

The structural weakness of the left parties persists in Central and Eastern Europe as well, though the increasingly differentiated political landscape is giving many on the left the opportunity to reconstitute themselves, such as Levica in Slovenia and the newly formed The Left in Poland, which includes the Democratic Left Alliance (SLD), Spring, and the left-wing Razem. At the same time, the Czech Communist Party (KSČM), which currently backs the government of billionaire and populist party leader André Babiš, lost half of its electoral base in the 2017 Czech Republic parliamentary elections. Overall, it is only by mandate that the left in these countries are represented at all in the European Parliament; though Levica’s positive results in Slovenia remained without a mandate. This promotes a strongly Western European view of the left and its political landscapes in the EU, although the increasing precariousness of Western European party systems could mean that Western European liberal democracies will find themselves moving closer to conditions in Eastern Europe.

GUE/NGL Results at the 2019 EP elections

Source: transform! europe EP19 Monitoring Project

Thesis 2:

The growing importance of left-wing parties in the struggles against austerity led not to the development of new political approaches or to a renewed capacity for intervention at a European level, nor to the development of either the PEL’s strategic competence or its mode of operation.

The founding act of the PEL took place in Rome in 2004. It was an attempt on behalf of the left to

- oppose the process of EU integration and the EU’s new neoliberal formation and its institutions with a left alternative

2. establish itself to this end as a new subject for the European left, closely linked to social movements and civil society initiatives and their experiences of new types of transnational organization. That was the aspiration.

Thus, after 16 years of its existence, the Party of the European Left faces considerable problems in its development. The PEL has been stagnating since 2014 and was unable to use the period of strong austerity protests as a window of opportunity to work out an alternative conception of the EU based on a fundamental critique of the EU treaties; the differences between positions on the EU within the PEL and the role of the EU left parties ultimately thwarted a common programme for action.

Source: European Parliament, own compilation

In the 2019 election campaigns, the PEL was unable to present itself effectively to the European public, neither at a strategic level nor in terms of its personnel. The failure to work out an alternative to the EU’s neoliberal development had lasting effects. As a result, the PEL’s demands for a fundamental transformation of the EU — through a renegotiation of the treaties in order to reorient the EU along more social, democratic, peaceful, and ecologically sustainable lines, while also developing a new economic and social model — remained largely abstract and without influence.

Thesis 3:

The fragmentation of the left at a national level affects its development at a European level, hindering transnational organization and the real capacity for intervention.

Since 2016, the fragmentation of the radical left intra-nationally has also had clear effects on its transnational organization. After the first round of French presidential elections in 2017, Jean-Luc Mélenchon (19 percent) was the leading candidate for La France Insoumise (LFI), the party he founded. However, he was unable to reach an agreement with the French Communist Party (PCF) over an alliance for the parliamentary elections in June 2017, and as a result the two parties are now represented in the National Assembly with blocs of almost equal size. These disputes directly affected the PEL – in 2018, Mélenchon and his Parti de Gauche left the PEL over its support of the Syriza government. In the 2019 European elections, LFI ran independently of the PEL. In the end, three left-wing projects were competing for left-wing voters: Maintenant du people with La France Insoumise, DiEM25 and the European Left Party – none was successful.

Whether these divergences can be kept in check in the future will be shown, among other things, by the new leadership of the GUE/NGL, which includes a representative of LFI (Manon Aubry) and a representative of Die Linke (Martin Schirdewan).

Thesis 4:

Differing or contrary attitudes towards the development of the EU make it difficult for the PEL to develop a coherent political approach within Europe.

The development of the PEL cannot be considered independently of the development of the EU. The implementation and tightening of the Treaties of Maastricht and Lisbon effectively function as a policy of memorandums in the Eurozone – especially towards Greece. The Stability and Growth Pact and other pacts have centralized European regulation into new forms of EU governance, directly affecting the social policies of its member states. This development has also promoted centrifugal tendencies, best represented by Brexit. Opposing developments collide: on the one hand, actors like Macron, striving to consolidate the EU, and on the other, the aspirations from the right to reduce the EU into a free trade zone. The left was weakened by its inability to intervene in these discourses effectively in 2018/2019, or in the controversies over the future of the EU; meanwhile the radical right gained strength.

Taking the West German left into account, in 2004 Richard Dunphy described the following possible responses left-wing parties could offer to European integration:

1) positing the EU as an agent of multinational capitalist exploitation and either German or US hegemony, fundamentally incompatible with a socialist or even slightly progressive programme;

2) accepting the above, but recognizing that campaigns for a withdrawal from or for the dissolution of the EU are unrealistic, and therefore demanding that it be fundamentally restructured;

3) criticizing the limited and restrictive nature of the EU’s existing institutional framework, but at the same time regarding the EU as a potential proponent of social progress. The key to reforming the institutions of the EU thus consists in a strong EU Parliament, which can enact laws and elect the EU Commission.

4) A “weak reformism” or uncritical pro-integrationism that aims to deepen European integration and create the United States of Europe based on a “historic compromise” between all pro-European forces from centre-left to centre-right.

The ideal type of the first position is championed by the Communist Party of Greece (KKE), but also with slight differences by the Portuguese Communist Party (PCP) and the EU-skeptical currents within the Nordic Green-Left parties, and is thus also represented within the GUE/NGL party in the European Parliament. In comparison, the majority of the PEL member parties (e.g. Die Linke, the French Communists, and Izquierda Unida) occupy a place somewhere between the 2nd and 3rd positions.

There are no left parties that adhere to the position of uncritical pro-integrationism described by Dunphy, and the experience of dealing with the Syriza government has rather led to an increase in Eurosceptic positions. The fact that the Troika’s third economic adjustment programme for Greece was pushed through despite resistance on behalf of the Greek government prompted the PEL to take an even more critical stance towards the process of European integration.

Due to the developments surrounding Brexit, by the 2019 European election, only a minority of the voices within the PEL were calling for a re-nationalization of policies. At the same time, the PEL parties are firm in their demands for the sovereignty of peoples — especially with regard to Greece. The question of how this position can form the basis for a left-wing response to the ongoing process of neo-liberal integration is open.

La France Insoumise proposed a collective exit (Plan A) or a national individual or partial exit oriented towards specific issues (Plan B). The movement Democracy in Europe Movement 2025 (DiEM25), founded by the former Greek Minister of Finance Yanis Varoufakis, has a different stance. They assume that, given the rise of right-wing radicalism, the re-nationalization of policies poses just as great a danger as the opaque, undemocratic structures of the EU and the Eurogroup. DiEM25 therefore calls for a radical democratization of the EU and the Eurogroup beyond an alternative monetary and economic policy.

The PEL oscillates between these positions and—combined with the fact that its positions are necessarily vague as a result of a compromise between the different positions within the PEL—has difficulties formulating a concept for a European alternative. Both Plan B and DiEM 25 have influenced the discussions within the PEL.

According to Gerassimos Moschonas, the great irony of the Europe policies of the left is that “they gradually accepted European integration, while the latter was becoming increasingly neo-liberal”. Most recently, austerity policies and the changes to EU primary law in the course of the economic crisis not only deprived any uncritical pro-integrationism of its basis, but at the same time changed the possibilities for leftist intervention. It is not only an ideological question of being “for” or “against” Europe. It raises the question of elementary strategic coherence: either the left decides in favour of a European strategy and deals with the political consequences; or it decides in favour of an anti-EU strategy (withdrawal from the union, restoration of national sovereignty) and deals with the resulting consequences. Opting for a European strategy would be incoherent, since it would mean either seeking solutions on a European level while continuing to use rhetoric oriented around the model of an insurgency; or opting for a “return to the nation” while claiming to be representatives of universalism and the world proletariat. There is, however, another option: to shift the strategic orientation towards anti-neo-liberal socio-ecological change at a national level, with the caveat of being willing to selectively break certain EU rules, to form alliances of the willing for and against this. The right-wing parties were successful in using this approach, at least when they all cooperated around the issue of migration.

Thesis 5:

The effectiveness of left-wing parties in centre-left or left-wing governments has a direct impact on the PEL.

The left parties’ participation in centre-left governments in the second half of the 1990s ended in devastating defeats, in both France (1997-2002) and Italy (1996-1998 and 2006-2008). Above all, the collapse of the Communist Refoundation Party, which also lost its parliamentary presence in 2008, impacted the European left more broadly, partly because Rifondazione was seen as the paradigm of a renewed radical left-wing party.

Support for the Syriza government hardly went beyond symbolic acts, although the negotiations between the Greek government and the troika (EU Commission, ECB, and IMF) stood for a fundamental debate about the European economic and social model. Greece became a test case for the intensification of austerity politics with the economic adjustment programs. The European left was neither able to prevent the Treaties of Maastricht and Lisbon from being passed nor to effectively counter the troika’s brutal approach.

At this point, the dilemma of the left parties since the 1960s became apparent: on the one hand, they have to secure their national strengths in the struggle for political power in order to be politically effective ‘at home’, i.e. to position themselves strategically, programmatically and organizationally at the national level, and at the same time—in view of the ongoing integration of the EU—establish themselves as a European actor, developing the necessary strategic foundations and adequate organizational structures for this at the European level. On top of that, the parties of the left must react to those challenges arising from the triple crisis of international communism, the Fordist social model, and neo-liberalism. This confronts left-wing parties with political, ideological, and cultural dilemmas: anti-neoliberal consistency versus centre-left unity; anti-neoliberalism versus anti-capitalism; and old traditions versus new realities.

The practice of the PEL

The principle of consensus determines the PEL’s practice. This was the indispensable prerequisite for its foundation. Since the party congress in Madrid in 2013 the procedure for electing the leading candidates, the delegates, and the executive committee of the party, for voting on their documents and procedures of the party congresses has been in place. Voting has become normal procedure. However, these votes are thought out well in advance in order to avoid fundamental disagreements with the potential to split the party at the congresses themselves. At the sixth congress of the PEL in Málaga in December 2019, for example, one of the most frequently formulated concerns up to that point was to push for left unity and not to question the consensus the working groups had reached on the political document and the evaluation report.

In the PEL’s evaluation reports from both its fifth party congress in Berlin in 2016 as well as the sixth party congress in Málaga in 2019, the party’s lack of ability to act and its lack of presence in the European public was emphasized, as well as the growing dissatisfaction of the PEL member parties. A first consequence of this was the decision to hold an annual European forum which would be open to progressive forces and parties, modelled after the Latin American forum in São Paulo. So far, this forum has not fulfilled these expectations. Like the PEL as a whole, its strategy, programme and organization must be further developed. The sixth party congress was not yet in a position to do so. Instead, this congress was used primarily to identify the urgent questions of today’s global developments, point out the European left’s pending tasks, and also to emphasize the necessity of developing the PEL. The congress postponed fundamental decisions, but nevertheless showed itself capable of reaching compromises in formulating common standpoints despite highly diverse views on the EU, and on alternative ways and forms of necessary cooperation. This is not enough, but it does enable the PEL to develop the space needed for a real change. This party congress produced optimal conditions for the PEL to transform itself.

In his speech as newly elected chair of the PEL, Heinz Bierbaum said that the Party of the European Left faces a double task: sharpening the party’s left-wing image and expanding its cooperation with various progressive forces in Europe. He also said that the ecological question presents new challenges which the left must work to link up with social issues and with the question of a new economic and social model.

It is now up to the parties of the left to decide whether the PEL should develop beyond a loose party alliance and into a more significant European political actor. To this end, the member parties must broaden the political consensus which forms the basis of their European party, and take up those discussions which have so far been avoided for the sake of maintaining political unity. The core question remains: which of the forms of democracy and self-determination identified in the PEL’s political documents from the congresses can be realized under the conditions of European integration? To this end and to avoid remaining in a “formal compromise”, a convincing realpolitik strategy, taking the real contradictions into account and containing feasible proposals for working through them, is crucial. It is up to them whether they succeed in meeting the new challenges and becoming an influential force for future developments, or whether they get caught up in the maelstrom of the political crisis that has gripped the entire European political system. They can still choose whether to be part of the “therapy”, or a symptom of European democracy’s decline.

Photo: Czechia is the only country of the Central and Southeastern Europe where the Party of the European Left has larger presence (source: Pixabay, CC0)

The Barricade is an independent platform, which is supported financially by its readers. Become one of them! If you have enjoyed reading this article, support The Barricade’s existence! We need you! See how you can help – here!