After Romania’s economy grew by 8,8% in the third quarter, the Bulgarian Economic Chamber came out with a document and reasons for their success. However, this thesis by the Bulgarian economic experts was surprising to their Romanian colleagues.

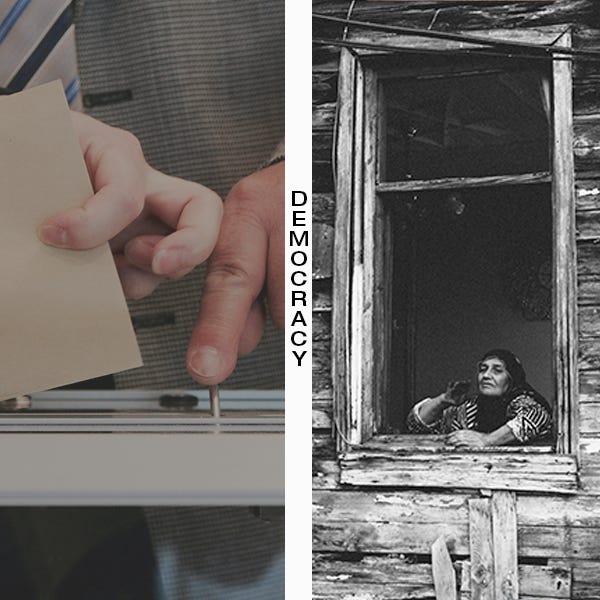

Romanians and Bulgarians have been comparing both countries economically for more than ten years. There is a simple reason for that – their economies and societies are comparable in various dimensions. Romania and Bulgaria will never become what Germany is and any comparisons with it could only bring dissatisfaction. But if a neighbouring country is a point of reference, one could get a relatively good idea about the direction that it is taking .

Romania and Bulgaria are “in the same boat”. The acknowledgement of this fact is the first step towards understanding where we are in the world economic processes. If Romanians and Bulgarians look at each other they will notice that there are plenty of similarities and only a few differences between their social realities. The economic model in both countries is the same: low direct taxes for capital, low income, reliance on foreign investments and a weak protection of labour. Foreign investors in banks, mines and distribution of electricity come from the same countries. It is no wonder that managers of international companies often are responsible for a region that classifies Romania and Bulgaria as one and also includes the Republic of Moldova or some other neighboring country.

A part of the comparison is the intrusive thought that our neighbour deals better with the bright capitalistic future’s construction. In Bulgaria, Romanians have become a byword for “overachievers”, because right-wing Bulgarians see their dreams by realised by their neighbours – the fight against corruption removes the dinosaurs of transition from the political game, economic growth is the highest in the EU, and a strong urban middle class was formed and it has adopted the role of taking the lead in its country’s modernisation.

It could be surprising to some Bulgarians, but to Romanians Bulgaria could also be an example of success. North of the Danube it is being regularly written, that Bulgaria has more kilometres of highways than Romania, that Sofia’s subway is being built fast, while Bucharest’s subway hasn’t opened a new station for quite some time and how Bulgarian tourism industry has become a subject of envy.

It even turns out that some Romanians have some faint sympathy towards Bulgaria. There is an opinion that national economic interests are better protected from the onslaught of foreign capital in Bulgaria. The site “Social Monitor”, which presents info graphics about various social indicators in Romania, Bulgaria and Germany unveils that the poor in Bulgaria are a little bit better off than the poor in Romania. One could probably reject such conclusions, but what matters is the tendency – on every side of the border to look for “salvation” or inspiration, as we face the mirror image of the neighbour.

In this context the Bulgarian Economic Chamber decided to contribute to the debates about the necessary economic and social reforms in Bulgaria, as it summed up some statistical indicators of Eurostat about Romania and Bulgaria. Romania looked like the example to be followed in the chamber’s document, which was distributed on its website and was shared further by the economic media such as Investor.bg. Romania had a record economic growth of 8,8% in the third quarter of 2017. Its unemployment rate in 2016 was 5,9%. The investment in its economy was 22,7% of GDP in 2016, while GSP/capita (in PPP) was 59% of the European average. In other words the chamber’s data list showed that Romanians are already moving on the highway of European well-being.

The same indicators on the Bulgarian economy were at more modest levels. The economic growth in the third quarter was 3,9%. Unemployment in 2016 amounted to 7,6%. Investment reached 18,6% of GDP, while GDP/capita (in PPP) was 49% of the European average (given that both countries joined the the EU in 2007 at levels of 41% of GDP). The whole picture resonated with the feeling of many Bulgarians that the country outside Sofia and few large cities is not developed and the people are paying the price for a wrong model.

The document also made a comparison which is hard to explain in this context. The annual net income per capita in Bulgaria in 2015 was only 6% lower that the Romanian one, while in 2007 the difference was 17,7%. It could be surprising to read that, against the background of previous data, because it means that Bulgaria kept good pace with the income growth. In fact this data suggests that in spite of the worse macroeconomic indicators, salaries in Bulgaria rise faster that in Romania so Bulgarians should be content and not demand more. But they should be worried because the economy might not sustain the rising incomes.

Whose income rises? Who benefts from the economic growth and who doesn`t? Why do statistics show dreams coming true, whilst many people who live in our two states are unable to save any money and have to that pray their health doesn’t deteriorate?

One could get lost in the world of comparison, if certain indicators are compared without understanding the context, which they reflect. That is why comments about the document of the Bulgarian Economic Chamber, presented by its vice president Dimitar Brankov in his interview for Bloomberg Bulgaria TV on 29 November 2017 needs to be studied with attention. He pointed out that the stronger sides of the Romanian model are the labour legislation reforms, undertaken after the world economic crisis, the flexible exchange rate of the leu, financial institutions` competence and foreign investments` attraction. If any of these elements is put in its Romanian context, it starts to look different.

The labour legislation changes of 2011 were introduced under pressure from the IMF, after Romania was forced to take loans of 20 billion euro from some Western financial institutions. These reforms undermine the labour unions, as they introduce the notion of the so-called „workers` representatives“ – a structure with severely limited capabilities for the protection of workers in their relations with the employer. That is how the reforms struck a blow to the social dialogue, and Romanians still can`t recover from this hit. It increased enormously the weight of capital in economic relations at the expense of salaried workers.

According to the Romanian social and economic expert Ştefan Guga the excellent economic growth of Romania today would have taken place without labour reforms too, because it has other causes: the success of the export-oriented sector of the economy, which relies on foreign investment and external markets. In fact, the GDP growth doesn`t mean that the whole population automatically gets richer or that public services become better.

Today in Romania two different economies exist – one of them foreign owned, and relying on foreign investors and external markets, and the other one – Romanian-owned, whose share in the overall economy has been falling after country’s entering into the EU. According to a survey by the experts of the Romanian national bank Florin Dragu and Adrian Costeiu on the period spanning 1994-2014, the companies with Romanian capital usually have business interactions with other Romanian-owned firms, while foreign-owned companies usually deal with other foreign-owned entities. Both authors conclude that only 7% of the companies with Romanian capital have realised 50% of turnover in relations between Romanian-owned and foreign-owned businesses, based in Romania.

These two parallel economies have different dynamics. The sector owned by foreigners in the Romanian economy comes with established technologies and markets and uses Romanians’ cheap labour and the low direct taxes for capital. This is an export-oriented sector and its orientation towards the external markets allowed it to grow a lot for ten years after joining the EU to the extent that in 2015 it had a larger share from the overall turnover in the economy than that of the Romanian-owned private sector.

According to 2015 data 22 146 exporting firms existed in Romania. These companies have sold goods worth 54,6 billion euro. The first 500 of them are responsible for 74% of these exports. The share for Romanian companies among these top 500 firms is only 10-12%.

This is the economy sector which creates big economic growth. The national capital sector usually relies more on internal demand which has been stimulated in the last years through the introduction of reduced VAT for foods (9%). Rising internal demand however increased the imports and created a larger trade deficit. The attempts to give tax preferences to various categories of citizens together with the rise of salaries in the public sector led to a situation, in which according to the European Commission in 2018 , Romania will have a budget deficit of 3,9% of GDP – above the threshold of 3% of GDP. That is why in an interview on the blog of Romanian economic expert Radu Soviani the Eurocommissioner for euro and social dialogue Valdis Dombrovskis said that Bulgaria had advanced “considerably” with regard to its entering in the eurozone, while Romania remained behind. In the middle of December 2017 the Romanian government unveiled its intentions to take a loan of 8 billion euro, which would be used in the following two years to fill in the holes in the budget

Even if Bulgaria has made progress, it remains limited to certain sectors and geographical regions. Joining the eurozone could become a stimulus for the introduction of reforms that could modernise the Bulgarian economy and society, as the economist Dimitar Sabev wrote in 2017. However no modernisation plan is on the horizon. Instead the Bulgarian government appears to hope to join the eurozone the way it joined the EU ten years ago – as a result of bargain, through obedience to Brussels and without making important social changes.

Romanian financial institutions are not accepted unanimously as very competent in Romania. As the Romanian economist Cornel Ban – professor at the University of Boston, points out – the Romanian financial institutions are the main highway through which the world economic crisis entered Romania at the end of the first decade of the XXI century. That is why their competence needs to be treated with a grain of salt, even though the Romanian National Bank has a lot of expertise.

Romania might not be in a currency board as Bulgaria is, but its last major currency depreciation vis-a-vis the euro was in 2008. In the last years the leu`s exchange rate has been relatively constant in relation to the European currency. In other words the country hasn`t received competitive advantages through currency depreciation for almost ten years. This autumn the exchange rate depreciated a little bit and reached 4,6 leu for 1 euro, but even this depreciation doesn`t appear to be very significant. Practically, the Romanian National Bank has been sustaining a stable exchange rate in relation to the euro as if the leu is pegged to the European currency.

It is true that Romania attracts more foreign direct investments than Bulgaria (70,11 billion euro against 23,5 billion euro as of 31 December 2016), but part of the explanation for that is not only in the larger dimensions of the country, but also its abundance of natural resources. They attract are like a magnet to big foreign interests. Our neighbours are not only open to foreigners, but they also worry that foreign economic interests are too well protected by the Romanian state, whilst the common man does not see the abundance in natural resources reflected in the price of fuel and in other aspects of their life.

Ştefan Guga points out that in the last years not only did salaries go higher in Romania, but also in parallel certain fiscal measures have been taken so that the labour expenditures don`t grow. An example in this regard is the case with the social security contributions transfer from the employers to the employees. As of 1 January 2018 employees will pay the greater part of social security contributions in Romania. That is why even though the minimal salary was raised to 1900 lei (around 400 euro) and income tax was lowered. Some categories of employees will be paid lower net salaries, while others will receive a symbolical rise in income. As our northern neighbours’ economy marks great economic growth, many people say that the Romanian employee has become a gradual slave of capital.

If anybody is looking for alternatives to the current economic model of social dumping in Romania what could they be? The switch to a developmental policy is often formulated as an alternative. It means that the economy must be transformed structurally so that it starts to produce goods and services with a high added value, and thus bring greater income to the state budget and a more equal distribution of income between capital and labour. According to Guga this vision includes also ”functioning public services accesible to more people… but it remains to be seen to what extent is this scenario viable from a political point of view in today`s context”. Such a development would mean other balances between the economic and political subjects in the country and beyond it. According to Guga this is utopian for the time being.

Surprisingly or not the Romanian economic model doesn’t differ a lot from the Bulgarian one. What is taking place in Romania has been used for years with political goals in Bulgarian social life. Knowing the Romanian context and the authentic Romanian opinions could help us understand better our own politico-economic realities. It could turn out that the desire to move to a “more Romanian” model, could lead to a “more Bulgarian” one.