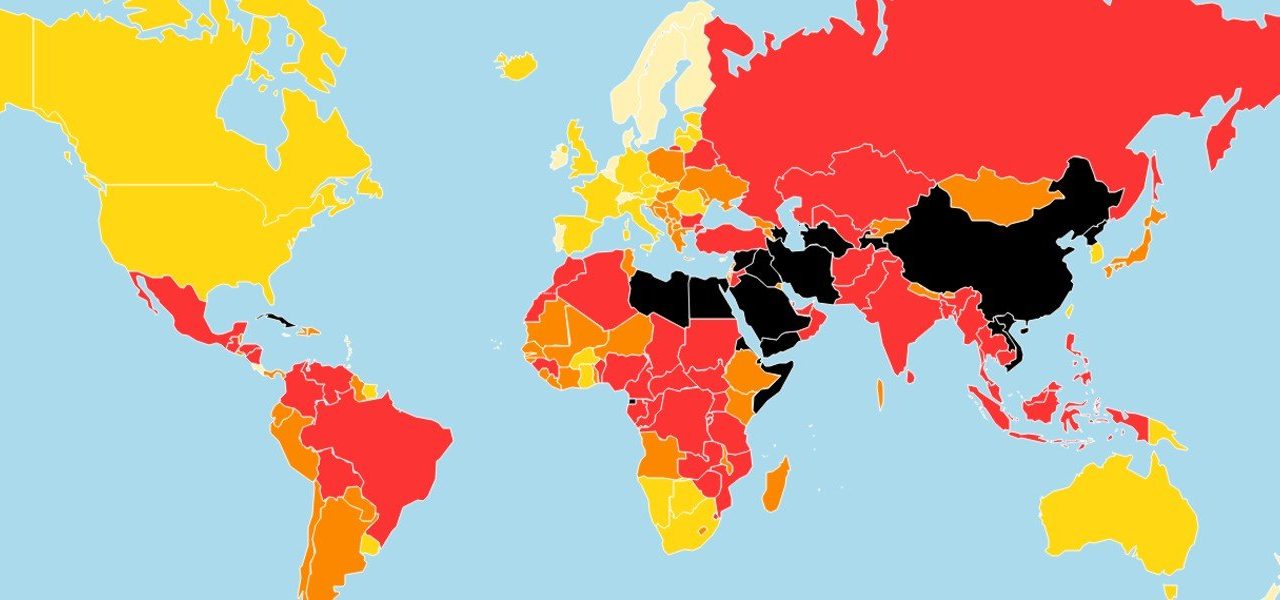

I could explain endlessly how desperate and hopeless the situation with the media in Bulgaria is, and how more and more often I regret that I took up the profession of journalism at all. That is why I am largely inclined to accept the grim findings in the Reporters Without Borders Press Freedom index, in which our country has been given an alarming 112th place this year. Excluding my objections to the presentation of certain oligarchic circles as selfless defenders of free journalism, the reports on Bulgaria present objective problems for the media environment — in fact, I would say that there are many more examples that could be added, even without going to the various attempts to pressure or slander the media of which I am a part.

But looking at the Reporters Without Borders map, in which countries are graded by colour according to their place in the rankings, I can’t help but notice how some obvious absurdities stand out. Despite all the points mentioned above, is it really justified for Bulgaria to be in the same category as Turkey, where most opposition media have been closed and prisons have been filled with representatives of the journalistic profession? Or to be in the same group with Myanmar, where the new-old coup junta is currently raging in a complete media blackout? And is the situation really any better in Ukraine, where the authorities recently took away the licenses of the three largest opposition media? Not to mention all the journalists there who have been killed, beaten, tried or forced to flee abroad in recent years.

These distortions are probably mainly due to the fact that the assessment largely reflects the ability of selected local media representatives to write dramatic reports – and the people who could write more dramatic reports for certain countries are simply not from the right circles, to be assigned this. And in this respect, it is difficult to say where censorship ends and where self-censorship begins.

I do not say this in the sense that Bulgaria should be higher up in this ranking — rather I believe that everyone should be lower down. In fact, at least the first 50 places in the index should be empty. Because there are other ways to restrict freedom of the press and speech, in addition to open state repression — and the result is often comparable, whether you assess the situation in yellow or red.

If virtually all the leading media are owned by a handful of big economic interests – whether we call them corporate or oligarchic — we cannot talk about true freedom of speech. If there is an almost unchanging consensus of positions and priorities between the leading media, economic and political elites, the security services and the intelligence agencies, there is no real freedom of speech. If certain views on economic, social and foreign policy issues — completely legitimate, but not shared by the “powers that be” — make the journalists into unwanted, “uninteresting” guests for the mainstream media, there is no real freedom of speech. If the consent production line rejects any internal attempt to object to the imposed consensus as the probable result of malicious “foreign interference” while at the same time it is propagating its own interference abroad as a credible expression of the aspirations of the local people, freedom of speech becomes a rather conditional concept.

And if the above conditions are present, there is a high probability that the reaction to the classic type of repression will be extremely dull, controlled or absent, regardless of the loudly proclaimed values. Because if journalists, publishers and their sources are in prison or in exile because they have exposed crimes of the authorities, there is no real freedom of speech. If, as a journalist, activist or just an audience, you are actively encouraged to take to heart the fate of dissidents in “enemy” countries, but you are ignored and marginalized if you do the same for your own country and its “partners”, the essence of “freedom of speech” is lost again.

And if referring to all this is considered almost obscene, unnecessary or dubious, then that in itself suggests that the problems with freedom of speech are probably deeper and more comprehensive than can be understood from the annual whining about the place assigned to us in the ranking of Reporters Without Borders.

This should not be seen as a call for the issue of media freedom to be rejected as unimportant or corrupted by organizations whose independence and impartiality are themselves in question. As with most leading humanitarian and human rights organizations, Reporters Without Borders has an interesting pattern — that very few of their positions actually receive broad coverage, or any coverage at all. Which suggests that much of the problem is rather in the media.

I have no doubt that a large number of the people involved in compiling this ranking have the best intentions — but they probably cannot or do not want to think outside the box, which makes the whole endeavour largely meaningless. Because if you see freedom of speech only through the prism of your own political, financial or ideological agenda, and not as a matter of principle, you are not really a defender of freedom of speech. If you justify inconsistency and double standards with “tactical” or “strategic” considerations, you are ultimately helping to undermine freedom of speech at both the local and global levels. Because if you lead this struggle selectively, you involuntarily or not, actually find yourself on the other side.

This article first appeared on the Bulgarian website baricada.org on April 22, 2021, and was translated into English by Vladimir Mitev.

Photo: World Press Freedom Index 2021 (source: rsf.org)