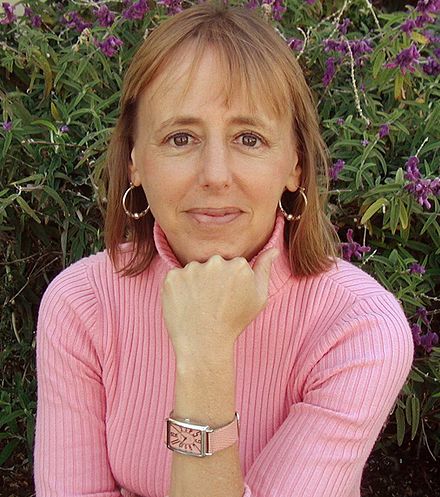

Review of the book written by Medea Benjamin

Medea Benjamin is one of the best-known peace activists in the United States. The author of thirteen books published by prestigious publishers such as Princeton University Press, ORBooks and many others, Medea Benjamin is a tireless opponent of militarism and war in all its forms.

A few of her published titles over her long career give us a glimpse of her concerns. In 1989 Medea Benjamin published three works, the first two of which she co-authored.

- “Bridging the Global Gap: A Handbook to Linking Citizens of the First and Third Worlds, Global Exchange / Seven Locks Press.

- “No Free Lunch: Food and Revolution in Cuba Today” Princeton University Press and finally

- “Don’t Be Afraid, Gringo: A Honduran Woman Speaks From The Heart: The Story of Elvia Alvarado. “Don’t be afraid, American: a Honduran woman speaks from the heart. The story of Elvia Alvarado. “Harper Perennial.

This debut book written by herself is followed by equally important works denouncing armed interventions and economic sanctions. We will mention only the most recent two. “Drone Warfare: Killing by Remote Control” ORBOOKS, 2012; and “Kingdom of the Unjust: Behind the U.S. – Saudi Connection” ORBOOKS, 2016.

Her prolific work as an author is complemented by an equally sustained peace activism. In 2002 she co-founded with Jodie Evans a well-known feminist pacifist organization called Code Pink: Woman for Peace.

In 2022 Medea Benjamin published “War in Ukraine: Making Sense of a Senseless Conflict,” with Nicholas J.S. Davis.

The paper has seven chapters and gives a rigorous overview of the main events related to the war in Ukraine. The main merit of the book is that it does not shy away from repeatedly blaming both Russia’s criminal actions and the provocations of Western states.

The story Medea Benjamin tells is not one of positive and negative heroes. The authors rhetorically ask two essential questions:

1. Does anyone really believe that Ukraine’s accession to NATO was such a threat that it could only be resolved by war?

2. Does anyone really believe that the best way forward for Ukraine was to totally ignore Russia and take advantage of its right to self-determination to join NATO as a matter of urgency?

The first chapter of the book describes the beginnings of the war in Ukraine and explains how the events of 2014 set the stage for the current conflict. Surely, there will be those who believe that analyzing

- history before 2022

- the role played by Victoria Nuland in the events known as “Maidan”

- the Minsk agreements

- how Ukrainian governments have dealt with minority issues and separatist regions

means:

- Russian propaganda

- relativisation of war crimes

- justifying the horrors of war in Ukraine, and

- collaboration with Russian secret services.

Well, if one judges by this scheme, one should stop reading this review and avoid the book. Unfortunately, there are still intellectuals in high-profile positions who judge this way. They think that quoting American experts who contradict the narrative or that discussing things from a broader perspective amounts to Russian propaganda. I don’t think they and those they persuade with their simplistic perspectives can be helped by reading. Their degree of bigotry and their black and white judgments are not to be countered with information. After the fog of war has cleared the cynics will be sifted from the gullible and their fairy tale of pretty girls from the West and fairy goddesses from the East will prove to be just another beautiful fantasy designed to support war at all costs. I repeat – on them we can only look with amazement and concern and send our good thoughts.

For those who want a serious analysis in which both the crimes of the Putin regime and the irresponsible reactions of Western leaders are unreservedly lambasted, this text and, obviously, the book are to be recommended.

As I said, the first chapter deals with the events leading up to the invasion of Ukraine and shows how even before 2014 there were prestigious American officials – such as former CIA director William J. Burns or the originator of the doctrine of containment George F. Kennan – for whom a NATO enlargement initiative was viewed with reluctance.

More interesting is the chapter in which American officials get directly involved in putting people favourable to them in charge: designating opposition figures with specific functions and duties in a post-Yanukovych government. The two agreed that Arseniy Yatsenyuk, or “Yats” as they called him, was the best choice for prime minister and that the opposition leader.

At the same time, a (now notorious) audio recording of US Assistant Secretary Victoria Nuland and US Ambassador Geoffrey Pyatt surfaced on YouTube. Vitali Klitschko and Svoboda’s Tyahnybok “and his boys” would be more useful “on the outside”. They discussed the difficulty of marginalizing Klitschko, who “was the main actor” in the Maidan. Nuland and Pyatt decided to present their plans directly to the new UN representative to Ukraine, Robert Serry, rather than discuss them with EU officials, who favoured Klitschko. Nuland said, “It would be great, I think, to get things going so that the UN can help us get this thing done and, you know, to hell with the EU.” Pyatt also talked about derailing Yanukovych and Russia, and agreed that “…We could land the cookie face up if we move fast … we want to try to get somebody with international notoriety to come in here and help us grind this thing out.”

Nuland responded (verbatim), “So on that note, Geoff, when I wrote the memo, [Biden’s national security adviser Jake] Sullivan got back to me VFR [very fucking quickly?], saying you need [Vice President] Biden and I said probably tomorrow, for some momentum and to get things [facts] going. So Biden is willing” (Benjamin, Davis 2022, 37).

The second chapter explains how the Minsk agreements were supposed to end a civil war in the Donbas region that resulted in over 14,000 casualties including 3,400 civilians, 4,400 civilian combatants and 6,500 separatist forces. There were two rounds of the agreement involving France and Germany. One in 2015 that ended the bloodiest phase of the conflict and one in 2015. According to the agreement, referendums were to be held in the separatist republics and they were to be granted autonomy, which never happened. The war itself has ended, although there have been numerous violations of the ceasefire agreement. Yet the economic war continued.

But the economic problems of the Ukrainian people only deepened as the new government launched a new round of privatizations and cuts in the public sector, as conditions for a USD 40 billion bailout from the IMF. Public sector wages and pensions were cut and public sector employment was reduced by 20%, while the health system and 342 state enterprises were privatized. Funding for public education has also been cut and 60 percent of Ukraine’s universities have been closed (Benjamin, Davis, 53).

Corruption-based regimes supported by Russia were replaced by other regimes, also based on corruption and this time supported by institutions advancing the idea of neoliberal shock therapy. Of course, the idea was, as the authors point out, for the new Ukraine to display an image of anti-corruption and self-determination in contrast to the outdated and corrupt Russian-backed leaders. Essentially the privatization measures only opened the way for Western capital to enter Ukraine. The country lost more than a quarter of its Gross Domestic Product between 2012 and 2016. The war only complicated matters because the breakaway regions were also the richest.

The paper gives a very accurate account of how events preceding 2022 have led to an unprecedented build-up of tensions. Elections should have been held in the breakaway regions. They were postponed. They were eventually held at the initiative of the separatist leaders, but were not recognized. Moreover, far-right groups, although poorly represented in Ukrainian voters’ choices, have become increasingly violent. The irony is that in 2015 the Ukrainian parliament was still able to narrowly pass a law on autonomy. Russia criticized it for not going far enough. But far-right leaders proved to be the most vocal: “…the right-wing Svoboda party opposed the autonomy granted to Donbas and staged a violent demonstration in front of the parliament building, which turned into a fierce battle with police and national guards. One National Guard member was killed, 122 people were hospitalized and 30 people were arrested, including a Svoboda member who confessed to throwing a hand grenade at security forces. Poroshenko called the violent demonstration a ‘stab in the back’ by his extremist partners in the post-coup government, and the bill never reached final passage” (Benjamin, Davis, 57).

The authors also focus on the figure of President Zelensky, who came to power in 2019 from the position of an actor on the show Servant of the People in which he mocked even far-right groups. The film of peace was broken when, after talks with France and Germany, President Zelensky ordered Ukrainian troops to withdraw heavy weapons from the separatist zone. But they resisted, pointing out that far-right elements, though fewer in number, wielded a great deal of influence, with power disproportionate to their numbers and political representation.

In October 2019, at a meeting with France and Germany in Paris, Zelenskyy signed a new agreement with Russia and the People’s Republics to withdraw heavy weapons from the line of contact in Donbas, exchange prisoners, grant autonomy to the DPR and the LPR, and cooperate on holding new elections, as agreed in the original Minsk II agreement. When some military units refused his order to withdraw, Zelenskyy went to Luhansk province, confronted the Azov Regiment troops on live TV and reminded them that he was the president and that he was ordering them to withdraw.

But far-right groups brought in volunteers from across the country to replace Ukrainian troops on the front line and set up armed checkpoints to prevent withdrawal. On 14 October, an estimated 10,000 right-wing protesters marched through Kiev, led by men dressed in black with white masks over their faces to conceal their identities. They carried red flares as torches and chanted, “Glory to Ukraine! We don’t surrender!” Faced with the same extremist forces as Poroshenko and no support for his peace initiatives from the United States, Zelenskyy abandoned his efforts. Like Poroshenko, he soon referred to the Donbas leaders as “terrorists” and refused to talk to them. (Benjamin, Davis, 64-65)

Chapter three concerns the invasion itself. The press provided coverage of the heinous war crimes and disasters that resulted from this first phase of the military operation that ended with President Zelensky admitting in June that Russia controls 20% of Ukraine’s territory. The authors condemn the invasion of Ukraine:

The first phase of the Russian invasion left death and devastation in its wake. Amnesty International has accused Russia of deliberate killing of civilians, rape, torture and inhumane treatment of prisoners of war. The organization also said Russian troops used indiscriminate weapons such as cluster munitions in populated areas. (Benjamin, Davis, 88)

These atrocities were responded to by escalating the conflict and using the opportunity to send even more weaponry into the war zone. In the pages of the paper the authors take stock of the tens of thousands of helicopters, drones, anti-tank weapons, grenade launchers, and other junk and equipment that have been supplied to Ukrainian troops. For the shareholders of arms companies like Lockheed Martin and Raytheon, the conflict has proved a huge opportunity. For Ukraine, the authors insist that the victory in Kharkov gave Ukrainians a sense of triumphalism. However, the cost in human lives is enormous.

A very important chapter is devoted to NATO. It is particularly useful reading for those who tend to idealize the role of this organization. The official narrative is that this is a defensive alliance and that it is being used by Moscow as a pretext because Ukraine would only be welcomed into the alliance after years of reform and progress. Of course, the arguments offered by the authors should be carefully followed. As far as we are concerned it is very important to remember that NATO is an alliance with nuclear weapons placed in Italy, Turkey, Germany, the Netherlands and Belgium. In addition, we Romanians and Poles have systems that can be converted into offensive weapons capable of sending nuclear missiles to Russia.

The authors make it very clear why NATO is an alliance whose intentions are far from strictly defensive. Moreover, relying on the right of self-determination, the alliance has added member countries that were never supposed to be in this position. There is a whole historical discussion about the promises made to Mikhail Gorbachev by Ronald Reagan when the Cold War ended. The authors explain how the intervention in Yugoslavia marked the transformation of the alliance into a purely offensive one.

This military intervention in the Bosnian civil conflict transformed NATO from a purely defensive alliance designed to deter or repel an attack on its members into a

an offensive one. In Bosnia, NATO used military force against an insurgent movement that did not attack or even threaten a NATO member. For decades afterwards, Bosnia remained a dysfunctional and impoverished part of the international community. The break-up of Yugoslavia led to an even more intense and controversial situation that resulted in a NATO military intervention in 1999. Presented as an attempt to stop Serbia’s ethnic actions in Kosovo, NATO launched a war – without the UN’s consent – to create an independent Kosovo from Serbia (Benjamin, Davis 2022, 107-108).

The authors insist on some very controversial and even tragic aspects of the bombing of Serbia in which 23,000 bombs fell destroying the infrastructure, including the TV building and the Chinese embassy. On the positive effects and the stopping of ethnic cleansing there are also dissenting opinions that the authors present. Lord Carrington, former NATO Secretary General and Chairman of the Board of the European Conference on Yugoslavia, denounced NATO’s handling of the situation, concluding that NATO had not only failed to prevent ethnic cleansing, but actually provoked it. (Benjamin, Davis 2022, 107-108).

In chapter five the authors discuss the unparalleled information warfare that began with Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Unsurprisingly, the Kremlin regime arrests and represses protests and critical voices. The law allows the regime to charge protesters and anti-regime protesters with terrorism and incitement to terrorism and to punish them with up to ten years in prison. More surprising, however, was the reaction of Western countries that prided themselves on freedom of expression and launched an unprecedented operation to shut down media outlets, social media accounts and YouTube channels on charges of propaganda. For years it has been based on the premise that citizens know how to choose and defend themselves. Suddenly, however, this omnipotence of citizens no longer mattered. What is interesting to note is that the paper brings into question the voices of opposition in the US and Russia. Few voices in Ukraine are heard, and Ukrainians advocating for peace are almost non-existent. Yet it is absurd to assume that in a country of 40 million citizens there are no such pacifist and anti-government positions.

Chapter six concerns sanctions and their effects. Of course, the thousands of sanctions on Russia have had the unintended effect of, probably, cutting off the trade in fertilizer and grain that the countries needed. African countries in particular have been deeply affected by supply disruptions resulting from the war. The authors present the situation in a balanced way. Of course Russia prides itself on not suffering from sanctions, but the dismissal of workers from companies that have left the country casts a different light on the situation. On the other hand, the US was counting on an immediate collapse of the Russian currency which, despite all expectations, has returned to pre-war levels. Each side presents a triumphalist view, but the authors insist that the truth lies somewhere in the middle. There is no clear victory in the sanctions war, but there are clear losses that unfortunately do not only affect the countries in conflict.

Finally, perhaps the most important chapter is the nuclear threat. The authors insist on pointing out that in Soviet times there were treaties preventing nuclear powers from dropping even one such bomb. In the meantime, American presidents have abandoned those agreements. In addition, the US is pushing for unrealistic expectations – the recapture of all territory. This is an extremely dangerous policy. The authors explain why. Russia’s conventional arsenal is smaller than that of the US. And because it cannot afford to lose this conflict after all the human and material effort it has made, Russia, pushed to the point of exhausting its conventional arsenal, will turn to nuclear weapons. The new regulations announced by President Putin make the interpretation that there is an “existential threat” rather lax. Tactical nuclear bombs, the authors explain, are merely a renaming of the destructive arsenal of unprecedented danger. Even dropping a few such bombs would risk a nuclear winter.

In conclusion, I think the most important phrase of the whole book, which is balanced and well researched, is this: unrealistic expectations. Right from the start, much of the Western public and most Ukrainians fell prey to rhetoric that promised things that were legitimate and perhaps desirable, but unattainable. Maintaining an illusion at the cost of the lives of thousands of Ukrainian soldiers is how Western powers have chosen to project their power and interests in the region. Fanatical warmongering and support for a war that can only escalate into a catastrophe seem the only options presented to us as legitimate. If you read the book written by the two authors you will perhaps better understand why peace and negotiations would be the way forward.

The Barricade is an independent platform, which is supported financially by its readers. If you have enjoyed reading this article, support The Barricade’s existence! See how you can help – here

Also, you can subscribe to our Patreon page. The Barricade also has a booming Telegram channel, a Twitter account and a YouTube channel, where all the podcasts are hosted. It can also be followed in Rumble, Spotify, SoundCloud and Instagram.